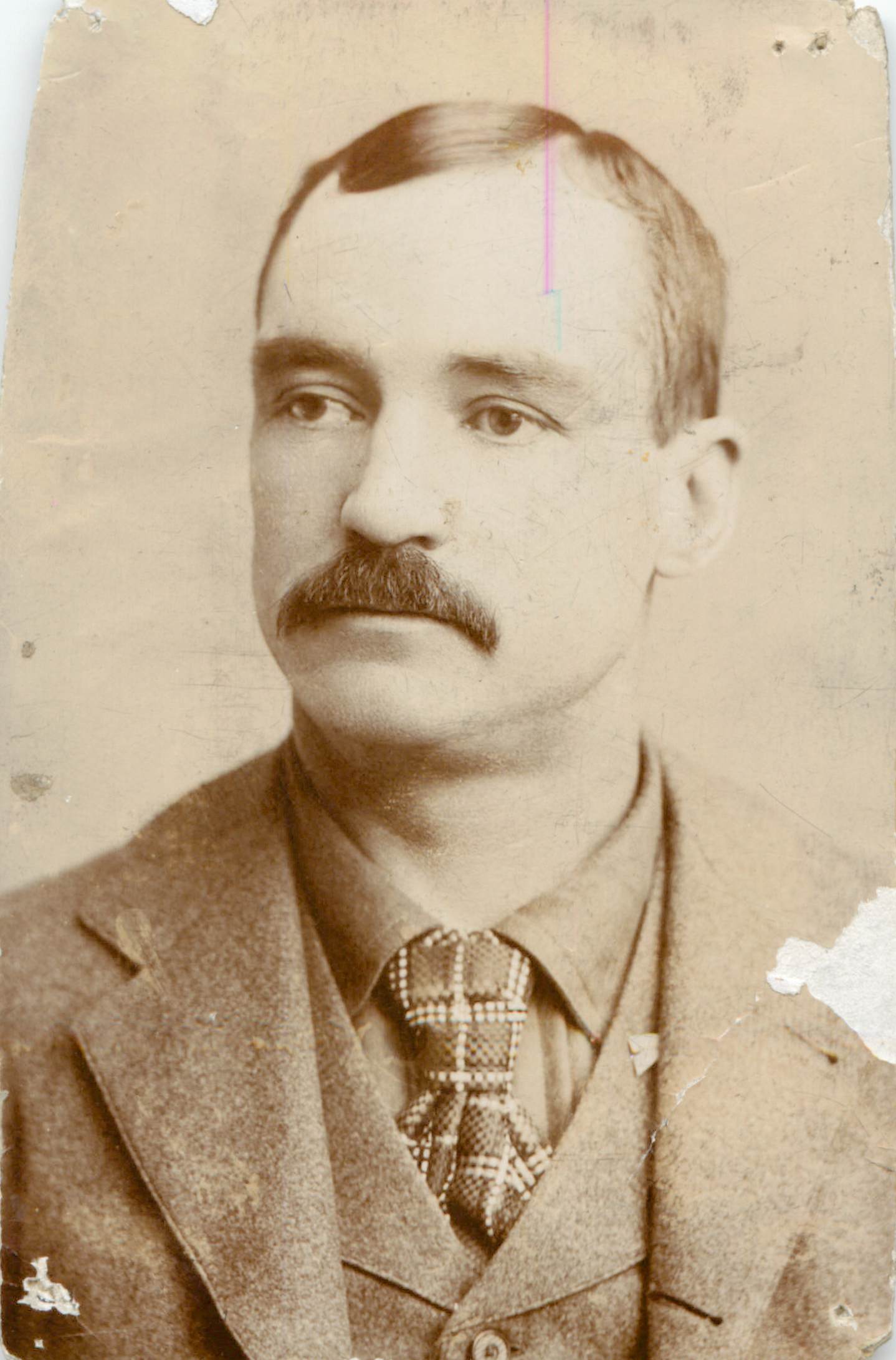

Edward Martin

Grandfather of Mae Martin Felt

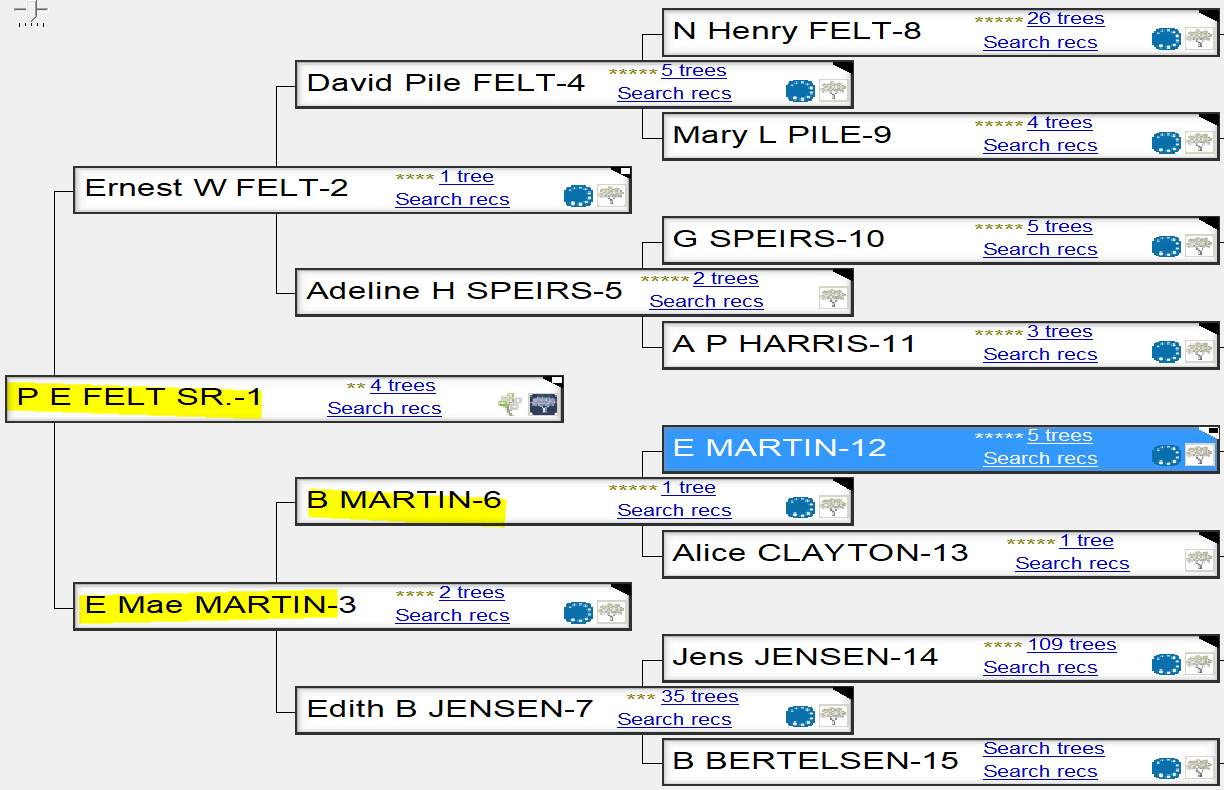

A view of the relationship helps understanding

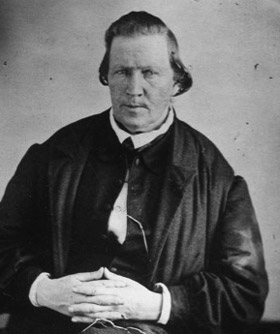

Edward Martin

A Younger Edward Martin

Martin Handcart Company

The Martin Handcart Company was a handcart company that crossed the plains to Salt Lake City in 1856. … The company consisted of 575 people, 145 handcarts, and 8 wagons, which were lead by Edward Martin. Due to the late start in the season, the company was caught in snow storms in Wyoming gs.

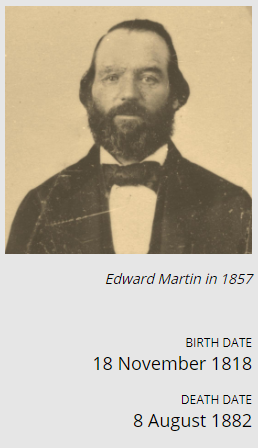

Edward Martin

Edward Martin initially travelled to the Salt Lake Valley with the Levi W. Hancock/Jefferson Hunt/James Pace/Andrew Lytle Company in 1847. He was the 3rd Corporal.

In 1848, he travelled with the Heber C. Kimball Company.

In 1856, he was Captain of the Edward Martin Company.

In 1863 he married Eliza Salmon in Salt Lake City. She had travelled on the ship “Horizon” in 1856 with Martin as the leader onboard. It is often mistakenly thought that she continued with Martin in the handcart company all the way to Salt Lake City in 1856. She did not. Her Mexican War widow’s petition claim affidavits explain that Eliza emigrated from England to St. Louis and married Thomas McCaughie (McCoy). Sometime after his death in 1859, between 1861 and 1863, she travelled on to Salt Lake with his daughter, Emma.

Music: King & Country – O Come, O Come

Now that we know the relationship

of

Paul Ernest Felt to Edward Martin, the

narrative by Edward Martin should be interesting

——-

Born: 1818 England Age 38 Captain of Martin Handcart Company

Father of: Mae Martin Felt who is the mother of Paul Ernest Felt (Sr.)

Edward was born in Preston, Lancashire, England, November 18, 1818. He joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in England and emigrated to the United States. He was one of the Saints called upon to defend his country as a member of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War. Later he was sent on a mission back to England and returning from there, he became Captain of the ill-fated Fifth Handcart Company of 1856.

The Fifth Handcart Company actually left Iowa City as two companies. Edward Martin was the Captain of one and Jesse Haven was the Captain of the other. They travelled separately until they reached Florence, Nebraska, where Elder Haven joined the Hodgett Wagon Company, and the two handcart companies combined under Elder Martin.

Captain Martin also brought a wife back with him from England, Eliza Salmon. Their first baby, George, was born August 12, 1856, in Iowa City, Iowa, while waiting for the handcart journey to begin. Edward and Eliza eventually had ten children. Two of Edward’s other wives died and Eliza also raised their children.

As the handcart company sought the shelter of the northern mountains in a ravine later to be named Martin’s Cove, they had many difficulties. It was a struggle for all of them to keep from freezing to death. Icy winds blew over a number of tents and many of the immigrants died.

One afternoon, Captain Martin, together with two or three other men, set out from the camp at Devil’s Gate, when they were surprised by a snowstorm and they lost their way. After wandering about for several hours, the men came near perishing and endeavored to make a fire to warm themselves. They gathered some cedar twigs and struck match after match to light them, but in vain. At length, with their last match and the aid of portions of their clothing, they succeeded in starting a fire. This was seen from the handcart camp, from which, after all their anxious and weary wanderings, they were only about a half-mile distant. Help soon came to the wanderers and the rescuers carried Captain Martin, who was nearly exhausted, back to camp.

There were many deaths in the camp. John Bond, a 12-year-old boy in Martin’s company recorded some experiences that give us a small idea of what leadership meant for Edward Martin: “. . . [Some died] lying side by side with hands entwined. In other cases, they were found as if they had just offered a fervent prayer and their spirit had taken flight while in the act . . . Some died sitting by the fire; some were singing hymns or eating crusts of bread . . . Captain Martin stood over the grave of the departed ones with shotgun in hand, firing at intervals to keep the crows and buzzards away from hovering around in mid air.”

Peter McBride, a young boy in the Martin Company, later paid tribute to Captain Martin in the narrative he wrote of their trek: “We had to burn buffalo chips for wood, not a tree in sight, no wood to be found anywhere. Just dry earth and rivers. We children and old folks would start early so we wouldn’t be too far behind at night. A great many handcarts broke down, oxen strayed away, which made traveling rather slow. Quite an undertaking to get nearly one thousand persons who had never had any camping experience to travel, eat, and cook over campfires. It took much patience for the captain to get them used to settling down at night and to get started in the morning.”

John Bond also recorded a time when a sister whose husband was near death and whose two sons were suffering with frozen feet, appealed to Captain Martin, ‘Do you think that the relief party will come soon with food, clothing and shoes?” Bond recalls that Captain Martin gave this suffering pioneer woman encouragement by answering, ‘Y almost wish God would close my eyes to the enormity of the sickness, hunger and death among the Saints. Yes, Sister Sermon, I am as confident as I live that the President (Brigham Young) will and has dispatched the relief valley boys to us and I believe that they are making all the haste they can, that they are bringing flour, clothing, shoes, etc.”

A day or two later, this sister, with faith in Captain Martin’s words, was looking into the west. All at once she sprang to her feet and screamed at the top of her voice, “I see them coming! I see them coming! Surely they are angels from heaven.”

Edward Martin lived in Salt Lake City and died there at the age of 64, on August 8, 1882. His youngest child was just eight years old. Eliza lived as a widow for 30 more years.

Our Honoured Pioneer Heritage

A Nine-Year-Old Girl Triumphed over the Handcart Tragedy

W. Paul Reeve

History Blazer, August 1995

The heavy morning frost on the Wyoming Plains west of Fort Laramie made walking unpleasant for those who were barefoot or in tattered shoes among the ill-fated 1856 Mormon handcart companies destined for Salt Lake City. Both the Willie and Martin companies replete with Mormon faithful eager to join fellow Saints in the Great

Samuel and Margaret

Fortunately, missionaries returning from England brought news of the destitute companies to Salt Lake City, and on October 5, 1856, Brigham Young dispatched a rescue team. Those immigrants who were still alive when help arrived were desperately cold or numb from the early winter freeze. Ephraim Hanks, one of the rescue party, recalled reaching several

At age 24 Nellie moved to Cedar City and not long thereafter became the plural wife of William Unthank. She bore six children and lived in poverty. She was, however, accustomed to facing challenges and did all in her power to make the most of her situation. Even while living in a log cabin she kept her home immaculately clean. She regularly dampened and scraped the dirt floor, making it smooth as pavement. To help meet her family’s needs she took in

As a fitting tribute to Nellie’s

See: Deseret News, August 4, 10, October 12, 1991; Rebecca Cornwall and Leonard J. Arrington, Rescue of the 1856 Handcart Companies (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1981); Leroy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen, Handcarts to Zion (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1960); Kate B. Carter, comp., Treasures of Pioneer History, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1952-57), 5:266-67.

Why our ancestors settled in Utah

Not just Utah for settlement expanded beyond Utah at the direction of President Brigham Young.

Some people disliked Mormon beliefs and practices and persecuted members of this church. After a mob murdered Joseph Smith in 1844, his followers started to think about moving somewhere where they could live peacefully. Enemies were still attacking Mormons in different ways. Because of this persecution, in the cold of February

The Mormon Battalion

James K. Polk

Because they had left behind their lands, buildings, and many possessions, the Mormons asked the federal government for financial help. The U.S. had declared war on Mexico in May 1846, so President James K. Polk agreed to enlist a battalion of Mormon men, who would receive pay for their service.

The Mormon Battalion at the Gila River in Arizona, a painting by George Ottinger (1833-1917).

Around 500 volunteers enlisted and began a

Their pay and their later explorations helped the Mormons become established in Utah.

Where to go next?

Meanwhile, the people gathered in Winter Quarters got ready to move again. Where to? It seemed that the Great Basin would be a perfect place to go.

Why?

Why?

The Great Basin lay far away from any government—in fact, this land belonged to Mexico at the time. (When Mexico lost the war, the United States took possession of the Great Basin.) Here, the Mormons hoped, they could live their faith in peace.

Mormon pioneers, sketched by Ortho Fairbanks.

In April 1847 the first group of Mormon settlers left and headed west along the California Trail. Brigham Young led a group of two children, three women, and 143 men. They

What other religious groups in U.S. or world history have moved all together to start a new colony? How are these different or the same as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

The Mormon migration

Between 1847 and 1869, when the Transcontinental Railroad was built, about 70,000 Mormons migrated to Utah along the Mormon Trail.

Many of them got help from their church. If they could not pay their way across the ocean, or across the plains, the Church’s Perpetual Emigration Fund might loan them the money they needed. When they arrived, they could pay off the loan so the money could help another immigrant. People

Salt Lake Valley in 1847, painted by H. Culmer.

Getting started in a new place.

Once the settlers arrived in the valley, the real work began.

Today, when most people travel to a place, they stay in a hotel or with friends, and they go out to eat at restaurants or buy food from a grocery store. But when the first pioneers arrived in Utah, the only people in the region were American Indians and a few explorers, traders, and mountain men scattered around. Basically, these new immigrants had to make or grow everything they would need in their new lives.

What would be the most important things to do first?

Right away, that first group of pioneers

They also built a fort where Pioneer Park now is. This fort had little cabins with sod roofs built along the wall.

Making a city.

Brigham Young directed that Salt Lake City (and other towns) be set up on a grid system. The streets were to run north-south and east-west. Young wanted the streets to be wide enough for two wagons to easily pass each other. We should be grateful for this, because of all the cars, bicycles,

Spreading out.

As the “Mormon Village” of Salt Lake City began to thrive and later groups of pioneers arrived, Brigham Young sent settlers to other areas of the state. He sent a variety of skilled people to each

By 1850, Mormons had started the communities of Bountiful, Farmington, Ogden, Tooele, Provo, and Manti. Each had a leader who had authority over both community and church affairs.

Sometimes, groups of people decided on their own to move somewhere and set up a community, without direction from the church.

By 1857, the Mormons had started more than 90 settlements.

Life in a new place.

Most communities also established an irrigation system. Why was irrigation so important?

At first, the new settlers built log cabins—or they lived in dugouts or even in their wagons for a while. When the communities got more settled, they could build houses and buildings out of stone, adobe brick, or brick

Many of these communities also built forts around their cabins for protection when Native Americans and the settlers were fighting.

The Mormon village in Utah was a planned community of farmers and

Source: http://ilovehistory.utah.gov/people/groups/immigrants/mormons/index.html

While Paul and Afton Felt resided in several locations, Provo was home

Situated in the heart of Utah Valley between the east shore of Utah Lake and the towering Wasatch Mountains is the city of Provo. Mount Timpanogos (elevation 11,957 feet) dominates the northern view from the city.

Other rugged mountains east of the city provide one of the most picturesque backdrops for a Utah city.

Utah Valley was the traditional home of Ute Indians, who settled in villages close to the lake both for protection from bellicose tribes to the northeast and to be close to their primary source of food–fish from the lake. The first white visitors to the Provo area were Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante, who visited Utah Valley in 1776. Only a retrenchment in Spanish New World colonization and missionary efforts prevented

Fur trappers and traders frequented the area in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and it is from one of these trappers, Etienne Provost, that Provo takes its name.

Provo was settled by our ancestors and others in

Provo remained the second largest city in Utah until Ogden became Utah’s primary railroad terminus in 1869. Provo lost in its bid as a transcontinental railroad stopping

In 1875 Brigham Young Academy was founded. From humble beginnings, this institution has grown into Brigham Young University, the largest church-affiliated university in the United States today. The city and the university have enjoyed a symbiotic relationship and have grown together. Today, the university has helped generate a high-technology industry in the Provo area and sometimes attracts national attention through its academic and sports programs.

Historically, Provo has served as the focal point of Utah Valley industry, commerce, and government. Agriculture and the Provo Mills (which had its origin in the LDS cooperative movement of the late 1860s) served as Provo’s commercial staples in the late nineteenth century.

Mining magnates such as Jesse Knight, made rich by nearby precious-metal mines, made their homes in Provo and helped create a thriving financial industry in the city. The coincidence of a major water source and the intersection of two railroad lines led to the completion in the Provo area of the Ironton steel mill in the early 1920s and later the much larger Geneva steel plant. The railroads brought in needed raw materials and transported finished steel products from Provo. Area residents currently argue about whether the Geneva plant, which many

As the county seat of Utah County, Provo is the home of county offices and courts. Since the mid-1880s Provo has been the home of the State Hospital, originally the Territorial Insane Asylum.

Because of its close proximity to the mountains, Utah Lake, and rivers, Provo residents have many recreational outlets. In winter, alpine and cross-country skiing, ice skating, and other winter sports are available within minutes. In summer, hiking, camping, fishing, and boating are equally accessible.

Provo residents have long been proud of their city. Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland, United States senators Reed Smoot (who also served as an apostle in the LDS Church) and William King; LDS Church apostle Dallin Oaks (who also served as president of Brigham Young University and as a justice of the Utah Supreme Court); Jack Dempsey, former heavyweight champion of the world, and numerous less well-known political, church, sports, and business figures have lived in Provo.

Today, Provo is a thriving community of 86,835 (1990 census). The city’s downtown heart is no larger the center of Utah Valley commerce, having lost that honor to large suburban shopping malls. Provo’s once proud train depot was recently demolished, a symbol of the declining importance of passenger rail transportation in the West. Provo’s downtown area remains, however, the focal point of Utah Valley political life, and nearby Brigham Young University remains the education center of the area. Provo has grown from a quiet, small Mormon city to a substantial modern metropolitan area. Some of its traditional quaintness is gone, but its heart and soul continue to thrive.

See: Kenneth L. Cannon II, A Very Eligible Place: Provo and Orem, An Illustrated History (1987); J. Marinus Jensen, History of Provo, Utah (1924); John Clifton Moffitt, The Story of Provo, Utah (1975); John Clifton Moffitt and Marilyn McMeen, Provo: A Story of People in Motion (1974); WPA Writers’ Project, Provo;Pioneer Mormon City (1942).

Edward Martin's Timline

Edward Martin’s Timeline

| 1818 |

November 18, 1818

|

Preston, Lancashire, England, United Kingdom

|

|

|

December 2, 1818

|

Wigan, Greater Manchester, England, United Kingdom

|

||

| 1844 |

March 12, 1844

Age 25

|

Springfield, Sangamon, Illinois, United States

|

|

| 1847 |

April 11, 1847

Age 28

|

||

|

November 28, 1847

Age 29

|

Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois, United States

|

||

| 1851 |

June 2, 1851

Age 32

|

Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah, United States

|

|

| 1858 |

August 4, 1858

Age 39

|

Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT, United States

|

|

|

August 6, 1858

Age 39

|

Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, UT, United States

|

Martin Handcart Company

The Martin Handcart Company was a handcart company that crossed the plains to Salt Lake City in 1856. The company faced extreme conditions in the fall of that year and were subsequently rescued by parties sent by Brigham Young at the October General Conference.

The company departed Iowa City on July 28, 1856. The company consisted of 575 people, 145 handcarts, and 8 wagons, which were lead by Edward Martin. Due to the late start in the season, the company was caught in snow storms in Wyoming in October. The group was rescued after taking shelter in a small cove, which was later called Martin’s Cove. The company arrived in Salt Lake City on November 30, 1856.

Source: http://lds.org/churchhistory/library/pioneercompany/1,15797,4017-1-192,00.html

Journey to Martin's Cove: Handcart Tragedy of 1856

In August 1856, in Florence, Nebraska Territory, two emigrant companies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—nearly 1,100 people led by Capt. James Willie and Capt. Edward Martin, left the Missouri River to start a late-season crossing of the plains. The Willie Company left Florence on August 17, the Martin Company on August 27.

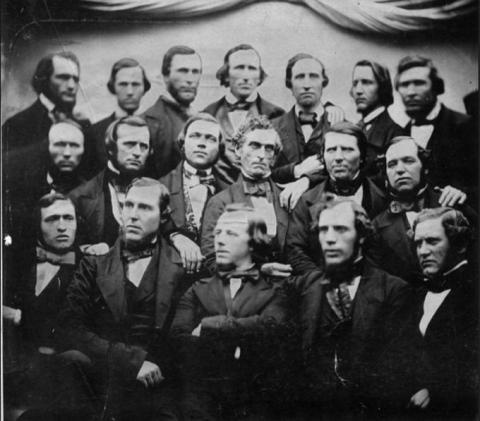

Mormon missionaries in Liverpool, England, 1855. LDS Church Archives. Edward Martin is on the extreme right of the middle row

Mormon missionaries in Liverpool, England, 1855. LDS Church Archives. Edward Martin is on the extreme right of the middle row

Four months later, the survivors reached

The

The 1856 emigrants were British and Scandinavian converts en route to the new Mormon homeland in Utah. The first Mormons had arrived there and founded Salt Lake City in 1847, after a decade and a half of increasingly violent persecution in New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois.

By the early 1850s, most American Mormons had already arrived in Utah, and the church began actively seeking converts in Europe. Church leaders organized a smooth transit system involving chartered steamships, riverboats up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and, later, railroad passage from the East Coast to central Iowa. Many emigrants’ passage was supported by the church.

In the mid-1850s, however, drought and famine struck Utah, and suddenly there was not nearly as much wealth in church coffers to support the incoming

The handcarts consisted almost entirely of green lumber and had been built in Iowa by the emigrants themselves. They were shallow, three feet wide and five feet long, and held skimpy supplies of food, plus 17 pounds of luggage—clothes, blankets, and personal possessions—for each person. A few ox-drawn wagons accompanied the party to carry tents, more food, and sick people. Rations were one pound of flour per person daily, plus any meat shot on the way. The carts were pulled by one or two people while other family members pushed behind or walked alongside.

Three smaller handcart companies had already crossed the plains to Utah quickly and successfully that year, with the help of supply wagons coming out from Salt Lake City. The crucial difference between these crossings and those of the Willie and Martin companies was timing.

Problems of late crossing

Levi Savage, a sub-captain in the Willie Company wrote in his journal that he warned the party before they left Florence of “the hard Ships that we Should have to endure. I Said that we were liable to have to wade in Snow up to our knees, and Should at night rap

However, Savage’s advice was ignored. He explained, “Brother Willey

Brigham Young about the time of the handcart tragedy. Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah

Brigham Young about the time of the handcart tragedy. Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah

Problems build and help prepares

Sometime in late summer, supply convoys from Salt Lake City were sent

But in early October, a party of

On October 19, the Martin Company crossed the North Platte River near present Casper, Wyo., where the trail left the river headed across

The water was shallow, but the river was wide and freezing cold. “[W]e had to travel in our

Rescue

Meanwhile, the rescuers were

A statue at Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City commemorates the handcart emigrants. Wikipedia photo

A statue at Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City commemorates the handcart emigrants. Wikipedia photo

Hanks and the other two scouts got the Martin Company moving again 60 more miles to Devil’s Gate. There, the rest of the rescuers waited for them at some abandoned traders’ cabins called the

Exhaustion, exposure and lack of food had weakened the emigrants of both the Willie and Martin companies, and many died even after rescue efforts had begun.

The Martin Company camped for several days in a small cove in the rocks that must have given some shelter from the wind, a mile or two east up the Sweetwater from Devil’s Gate. They still had very little food. Two small Mormon wagon trains that had been

Besides personal belongings, the smaller trains were also carrying commercial freight bound for Utah. A solution became obvious: empty these trains of most of their goods, leave the goods behind at the traders’ cabins, abandon the handcarts, and give the weakest members of the Martin Company a ride the rest of the way. Twenty men stayed at Devil’s Gate to guard the wagon-train goods for the rest of the winter.

With the help of more rescue parties sent east, the Willie Company finally reached Salt Lake City on November 9 and the Martin Company on November 30. A modern historian counted 67 deaths in the Willie Company, a rate of around 14

It was by far the worst non-military disaster on the emigrant trails. Of the 60,000 or so emigrants who

Souce: https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/journey-martins-cove-mormon-handcart-tragedy-1856

Mormon Handcart Pioneers

The Handcart Pioneer Monument, by Torleif S. Knaphus, located on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah

The Mormon handcart pioneers were participants in the migration of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the LDS Church) to Salt Lake City, Utah, who used handcarts to transport their belongings.[1] The Mormon handcart movement began in 1856 and continued until 1860.

Motivated to join their fellow Church members in Utah but lacking funds for full ox or horse teams, nearly 3,000 Mormon pioneers from England, Wales, Scotland and Scandinavia made the journey from Iowa or Nebraska to Utah in ten handcart companies. The trek was disastrous for two of the companies, which started their journey dangerously late and were caught by heavy snow and severe temperatures in central Wyoming. Despite a dramatic rescue effort, more than 210 of the 980 pioneers in these two companies died along the way. John Chislett, a survivor, wrote, “Many a father pulled his cart, with his little children on it, until the day preceding his death.”[2]

Although fewer than 10

More: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mormon_handcart_pioneers

Pioneer Story-Captain Edward Martin

Pioneer Story – Alice Walsh Strong (Martin Company)

We left on the 26th of July and

At night in our

Our rations had to be cut down both for adults and children and the clothing of both sexes becoming

Arriving at Devils-Gate about the first of November on account of the nightly fatalities of the male members of our company, for two or three weeks previously, there were many widows in our company and the women and children had to pitch and put up the tents,

My husband [William Walsh] died and was buried at or near Devil’s Gate and the ground was frozen so hard that the men had a difficult task in digging the grave deep enough in which to inter him, and nine others that morning, and it is more than probable that several were only covered over with snow. Here I was left a widow with two young children. The boy [John Walsh] became so weak, he could not stand alone and I had to sit and hold both of them in the relief wagons from this on. At times the most of us had to walk after being met by the teams from Salt Lake and late in the day, and toward evening my shoes would nearly freeze to my feet and at one time in taking them off some of the skin and flesh came off with them. Some of the bones of my feet were left bare and my hands were severly frozen.

When the relief help reached us and nearly all of us had been assigned to some wagon I was sitting in the snow with my children on my lap, and it seemed that ther was no chance for me to ride, but before the last teams had left the camp I was assigned to ride in the commissary wagon, and did so until our arrival in Salt Lake City.

The young man in charge of the commissary wagon, was, Joseph B. Alvoard; seemed to be well acquainted with frontier and mountain life and realizing my condition of a widow with two children, he helped me early and late to the best of his ability.

Arriving in Salt Lake Nov. 30th 1856, with two children and the clothes I stood up in, were all of my earthly possessions in a strange land, without kin or relatives; the extra clothing we had started with and pulled on our carts to the Devils Gate, was left there and I never saw it afterwards.

Samuel Washington Orme story of Martin Company

Samuel’s parents, Samuel and Amy Kirby Orme, first emigrated from England around 1831 to live near Amy’s parents in Ohio. It was at this time that the first gathering of the Saints was occurring in nearby Kirtland. Samuel Orme, Sr. heard some men preaching the gospel in a town near Mentor and was impressed with the truth of their message, though he did not learn the names of the men or the religious sect to which they belonged.

The only son born to Samuel and Amy was born in Ohio on Independence Day. His parents felt that in addition to carrying his father’s name, he should have an additional name suggestive of this great event in American history. Accordingly, he was named Samuel Washington Orme.

Shortly after Samuel’s birth, the family returned to England to assist Grandfather John Orme, who was in his declining years and wished his son to return. The family moved to Coalville where young Samuel remembered his father taking him and his younger sister by the hand and going a short distance to see the first train go through Coalville. Samuel, Sr. was a bookkeeper for the Midland Railway Company.

When Samuel W. was 9 years old his father died. Samuel W. became an apprentice to a blacksmith for the next 7 years and also worked in the nearby coal mine. He was an excellent penman and learned somewhat of his father’s trade, but did not become a bookkeeper. He finally earned enough money at his blacksmith’s trade that he supported his mother and sisters comfortably.

Before Samuel Orme, Sr. died, he reminded his wife about his strong impressions of the preachers back in Ohio. He had studied the Bible, pondered about it, and knew it was true. He told his wife that she must join this church whenever she heard about it. He said, “When you hear the first sermon, you will feel as I feel, that it is true. A strange spirit will come over you, and you shall feel as if the truth of it is burning into your very soul.” Only a few months after Samuel’s death, Amy heard of two brothers, John and James Burrow, who

They boarded the ship Horizon in Liverpool with a large company of other Saints bound for Zion under the direction of Edward Martin, a returning missionary. Martin’s handcart company was organized in Iowa City, Iowa. It was the 5th and last handcart company of the year. The Hodgett and Hunt Wagon Companies were following closely along, and assisting as much as possible. However, because of their delayed start and early winter storms in Wyoming, they all suffered together from hunger and cold.

As flour rations were cut, and then cut again before the rescuers came from Salt Lake City, the Orme family was down to four ounces per day per person. Samuel’s courageous mother saw her son quickly weakening. She proposed to her girls that they each cut their own rations even further in order to feed Samuel more. They all agreed to make this sacrifice and it saved Samuel’s life. His sisters and mother also survived, although Rebecca had to have several toes amputated.

Samuel had left his sweetheart, Sarah Cross, in England. She emigrated the next year and she and Samuel were married. They soon moved to Tooele where Samuel became prominent in the community, serving in many positions in the church and community, including mayor of Tooele two terms without pay. He was an earnest advocate for better schools and did much work as a trustee. Samuel died in 1889 at the age of 57.

Patience Loader recall her experience

James and Amy Loader came to America in 1855. James had worked in England as foreman and head gardener for a wealthy gentleman by the name of Sir Henry Lambert. Patience and her eight sisters and four brothers were all born here on this estate where James had worked for 35 years. Somewhere around 185O, the Loaders were baptized members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. James was fired from his job as a consequence. In November 1855, they left for America on the “John J. Boyd” with at least six of their unmarried children, including Patience. Their oldest daughter, Ann (Dalling), had already emigrated with her husband and was awaiting their arrival in Utah.

Patience recorded a rather precarious and interesting experience she had upon her departure from England: “After my parents and my sister and I got all our baggage on board the ship, we found that it would not sail until the next day, so I decided to go back to stay at my married sister’s house that night. The next afternoon I went back to the ship and found it ready to depart. The men were just taking away the last plank. There were all my folks standing on deck watching anxiously for me and shouting at the top of their voices, ‘For Lord’s sake bring our girl on the ship and don’t leave her behind.’ There was just one plank to walk on from the dock to the ship and father and mother were afraid I should fall off into the water.

“The sailors said, ‘Miss, do you think you can walk the plank?’ I told them I thought I could, but they thought I might get dizzy and fall off so they were very kind. One man went on the plank before me and took my hand, the second man came behind me on the plank and took my left hand. They said if I slipped they would save me from going into the water . . . There was great anxiety among them when they saw me walking the plank with the sailors, and there was great rejoicing when I was safe on the vessel with them.”

The Loader family first went to Williamsburg, New York, where they all worked for a time. Even their daughter, Sarah, who was not yet twelve, worked as a nursemaid in the home of a wealthy family by the name of Sawyer. They left in June of 1856 and traveled to Iowa where they joined with their daughter, Zilpah, her husband, John Jacques, and their one-year-old daughter, Flora. Zilpah was expecting another baby, which was born on the plains in August. This new baby, Alpha, survived as (eventually) the longest-lived member of the Martin Company, but little Flora did not survive the trek. She died about a week before reaching the Valley.

One family record indicates two sons coming to America, but only ten-year-old Robert is listed with the Company. Robert died on the plains. James also died, fairly early in the trek, leaving his wife and daughters to finish the trek alone. The rest of them survived the trek, experiencing many miracles amid their tribulation. James had been faithful and courageous in defending his new faith. One of his greatest wishes was to see his daughter, Ann, in Zion. Surely the Lord granted James this blessing of witnessing his entire family in Zion.

Patience was blessed with a mother who was a very strong woman. She protected, sustained and cheered her children as well as others without complaining, and manifested great faith in God. She put on all the extra clothing she could carry under her own, so when the children needed dry clothing, she always had it, including dry stockings for them after fording streams. As the weather became colder and provisions shorter, they were given four ounces of flour a day for each person. Instead of the usual gruel, Mother Loader made hers into little biscuits and would have them through the day, thus having a bite or two for the children when they were tired and faint.

One day, a man lying by the roadside, when asked to get up, said he could not, but if he had a mouth full of bread he could, so Amy gave him some food and he got up and went on. In Salt Lake some time later, this man stopped Amy and thanked her for saving his life.

After one exceptionally cold night, Amy (whose health was also very fragile), could not get her daughters to arise. She finally said, “Come girls, this will not do. I believe I will have to dance to you and try to make you feel better.” Amy struggled to her feet, hair falling about her face as she filled the air with song. Louder and louder she sang, her wasted frame swaying as finally she danced, waving her skirts back and forth. The girls laughed, momentarily forgot their frozen toes and snow-covered blankets, as their mother danced and sang and twirled until she stepped on an ic,v patch and fell in a heap to the ground. Then, Patience wrote, “. . . in a moment we was all up to help our dear Mother up for we was afraid she was hurt. She laughed and said, ‘I thought I could soon make you all jump up if I danced to you’. Then we found that she fell down purposely for she knew we would all get up to see if she was hurt. She said that she was afraid her girls was going to give out and get discouraged and she said that would never do to give up.”

Patience had a sister, Tamar (22), who was very much grieved when she left England because she had been unable to convert her sweetheart and he remained. One night, while on the plains, after much grieving, she had a dream. The next morning she told her mother that she had dreamed that her sweetheart came and stood beside her and he seemed so real. But he was not alone. Another man was with him . . . In the dream the sweetheart finally faded away but the other man remained. When Tamar first saw Thomas E. Ricks in the rescue party, she took her mother by the arm and said, ‘Mother, that’s the man.” She did marry Thomas Ricks (after whom Ricks college was named).

Patience also had spiritual experiences on her trek. She relates that one day as she was pulling the handcart through the deep snow, a strange man appeared to her: “He came and looked in my face. He said, ‘Are you Patience?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘I thought it was you. Travel on, there is help for you. You will come to a good place. There is plenty.’ With this he was gone. He disappeared. I looked but never saw where he went. This seemed very strange to me. I took this as someone sent to encourage us and give us strength.” (The Loader family was met by rescuers at camp that night.)

Patience also wrote: ‘We did not get but very little meat as the bone had been picked the night before and we did not have only the half of a small biscuit as we only was having four oz. of flour a day. This we divided into portions so we could have a small piece three times a day. This we eat with thankful hearts and we always as[k] God to bless to our use and that it would strengthen our bodies day by day so that we could perform our duties. And I can testify that our heavenly Father heard and answered our prayers and we was blessed with health and strength day by day to endure the severe trials we had to pass through on that terrible journey before we got to Salt Lake City. We know that if God had not been with us that our strength would have failed us . . . I can say we put our trust in God and he heard and answered our prayers and brought us through to the valleys.”

Martin Handcart Company: Sarah Ellen Ashton

Day Saints and they made plans to sail for American. Sarah’s parents, William (33 or 34) and Betsy Barlow Ashton (33), their children Betsy (11), Sarah Ellen (10), Mary (4), and Elizabeth Ann (1 or 2

While at sea (or in Boston), Sarah’s sister, Elizabeth, died. The family arrived in America and

They

After this sad tragedy, Sarah’s father became discouraged, left his three little girls with the company, returned to New York, and later went back to England. The Saints cared for the little girls as well as they could. They all suffered greatly from food shortages and the lack of warm clothing. Sarah Ellen’s oldest sister, Betsy, froze to death. This left Sarah and her sister, Mary, to continue walking on to the Salt Lake Valley. They arrived on November 30, 1856.

They were met by a group of Saints who took them in and cared for them. Later, they found a home with the Hatfield family in Farmington, Utah. They remained there until Sarah married Thomas W. Beckstead when she was 15. Sarah and Thomas had 10 children, four of whom died as infants.

Sarah devoted her life to her children, her husband, and her church. In 1887, the Beckstead family moved to Idaho. Sarah read in the paper where her father was advertising for his family. Sarah Ellen sent to England for him to come and join her family. Sarah’s father accepted her invitation and Sarah cared for her father until his death.

Sarah Ellen lived a good life helping the sick and needy. Surely, she learned to trust in God and be forgiving. She lived to be 92.

Martin Company: Pioneer Story-Mary Barton

Understanding

Understanding may lead to new insights

Experience

Understanding Past Lessons from others can